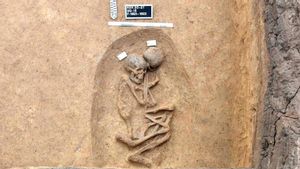

JAKARTA - A surprising result was obtained when a group of archaeologists re-examined one of the oldest burial sites in the world, Jebel Sahaba, which is located on the east bank of the Nile, North Sudan.

In a statement on Thursday, May 24, researchers who re-examined the remains from the 13,400-year-old Jebel Sahaba cemetery in 1960, revealed new facts about prehistoric bloodshed.

Including shocking evidence, there has been a series of violent acts rather than a single deadly clash as is widely believed.

Of the skeletal remains of 61 men, women, and children, 41 had signs of at least one wound, mainly from projectile weapons, including spears and arrows. Some of the wounds had healed, indicating the person had survived the battle.

Sixteen of them had healed and unhealed wounds, indicating that they survived one fight only to die in another. Microscopic examination identified the wound with the remains of a stone gun embedded in the bone.

Previously, the original analysis in the 1960s had identified only 20 people with wounds and none of the wounds healed.

Widespread and indiscriminate violence affects men and women equally, with children as young as 4 being injured too," said paleoanthropologist Isabelle Crevecoeur of the French National Center for Scientific Research at the University of Bordeaux, lead author of the study published in the journal Scientific Reports.

"It seems that one of the main lethal properties to look for is slashing and causing blood loss," Crevecoeur said.

While spears and arrows can be fired from a distance, there is also evidence of close combat with multiple hand fractures, blows to the forearm held back when the arm is raised to protect the head and hand fractures.

Hunter-gatherers lived in the Nile Valley at the time, before the advent of agriculture. They hunt mammals such as antelope, catch fish and gather plants and roots. Their group was small, perhaps no more than a hundred individuals.

While it's hard to know why they fought, it was during times of climate change in the region from dry to wet periods, along with episodes of severe Nile flooding, that probably sparked competition among rival clans for resources and territory.

"Unlike certain battles or brief wars, violence seems to have become a regular occurrence and part of their daily lives," said study co-author Daniel Antoine, acting head of the Department of Egypt and Sudan and curator of bioarchaeology at the British Museum in London, England.

Crevecoeur said archaeological evidence suggests "repeated small-scale clashes may have taken the form of raids, skirmishes, ambush attacks among hunter-gatherer groups, rather than a single conflict." Unknown cultural differences between groups could also play a role, Crevecoeur added.

The site, now submerged beneath a massive man-made reservoir called Lake Nasser, is the earliest known ancient burial complex in the Nile Valley and one of the oldest in Africa. Human remains have been kept in the British Museum.

SEE ALSO:

Philosophers have long pondered the contradictions of human nature. Our species has forged extraordinary intellectual, technological, and artistic achievements and has engaged in terrible wars.

Archaeological evidence has shown interpersonal violence in human evolutionary lineages even before the appearance of Homo sapiens more than 300,000 years ago.

"We believe our findings have important implications for debates about the causes and forms of warfare. To be sure, acts of violence date back hundreds of thousands of years, and are not limited to our species, such as Neanderthals, for example. But their motives may be as complex and diverse as we can imagine," he concluded.

The English, Chinese, Japanese, Arabic, and French versions are automatically generated by the AI. So there may still be inaccuracies in translating, please always see Indonesian as our main language. (system supported by DigitalSiber.id)