JAKARTA - Anti-Chinese sentiment seems to be deeply rooted in various parts of the world following the outbreak of COVID-19. In Canada for example. In this year alone, the Canadian police have received 20 reports of cases of hate speech and attacks against citizens of Chinese descent who are allegedly closely related to the virus originating from the mainland of Wuhan.

On that basis, not a few people condemned the action. However, if you look back a little, anti-Chinese sentiment is not only developing in Europe. In Indonesia itself, this anti-Chinese sentiment actually thrives. Starting from the 98th Tragedy to the most recent election for the Governor of DKI Jakarta several years ago, which always positioned Chinese people as the target of racial sentiment.

So, to minimize this incident, at least the Indonesian people could learn from the beginning of a long history of sentiment towards Chinese people in 1740, known as Geger Pacinan. This is because the past is always actual as a learning material, so that the public can learn from the sentiment that led to the assistance of around 10 thousand Chinese people in Batavia.

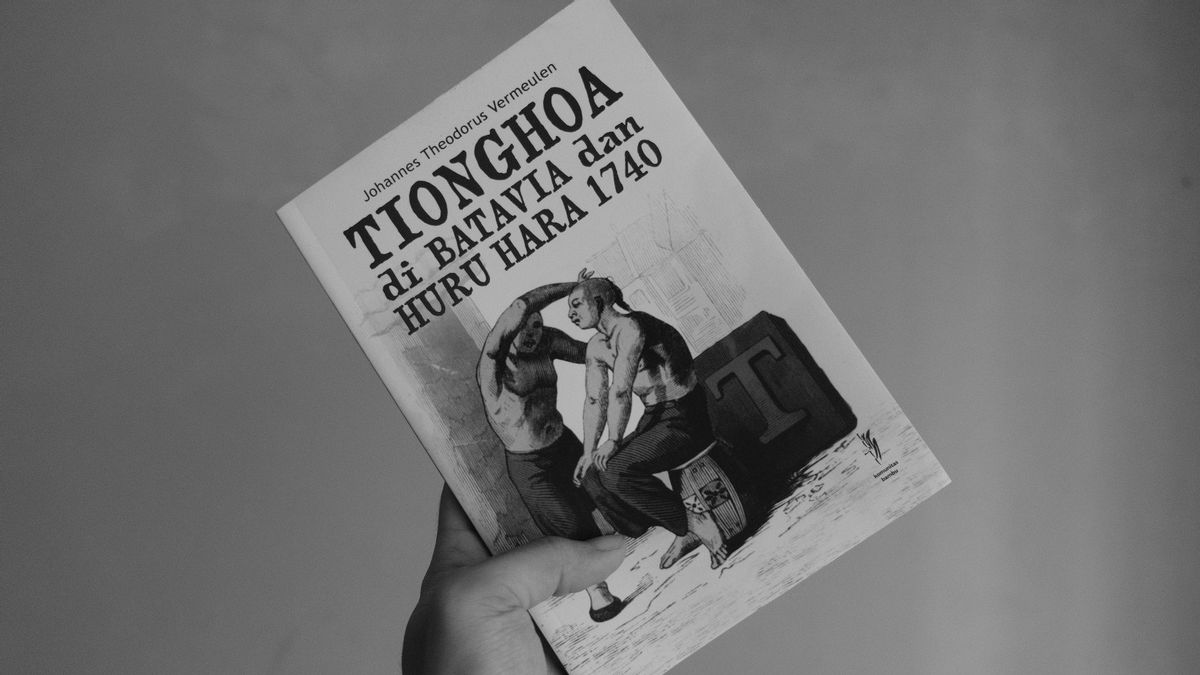

Then, we should be grateful to the VOC Archivist Johannes Theodorus Vermeulen. Thanks to his book entitled Tionghoa di Batavia and Huru Hara 1740 (1938). At least, readers will not half-understand how racial sentiment was formed, the influence of rumors, riots in Batavia, and the impact the Dutch had to pay for.

Not surprisingly, this book is the main reference for those who want to know about the incidents of the Chinese ethnic massacre in its entirety. Especially, for those who want to see the incident at length, so that those who read it will think long before labeling racial sentiments to certain ethnicities. Here's the review:

First, the beginning. In this section the reader is invited to find out the extent of the role of the Chinese in Indonesia, especially in Batavia (Jakarta). From the start, the Chinese people have been welcomed by the local community because they generally have a hardworking nature and don't like war.

Moreover, along the way, the Chinese who settled and married local residents made them embrace Islam as a religion. On that basis, they were completely welcomed by the residents of the Land of the Emerald Equator.

To the point, when the Dutch, through a VOC trading partnership, began to colonize Indonesia in 1619, the Company was attracted to the tenacity of the Chinese in its presence. On this basis, the Company also welcomed it by granting various privileges if there were Chinese who wanted to stay in Batavia. Why? Because the only thing in the VOC's brain at that time was only thinking about how to make profit.

“The Governor-General of the VOC, Jan Pieterszoon Coen immediately realized the importance of increasing the number of Chinese and making them the majority of the new population. the visualization of the young republic made him realize a few years later that: no other nation can serve us as well as the Chinese, ”writes on page 7.

Second, the cause of the 1740 rebellion. Like a relationship built on a profit-loss basis, when the VOC's income began to decline as it lost competitiveness with the British trading partner, the East India Company (EIC). No wonder this has an impact on the breakdown of the harmonious relationship that has been built for years by both parties.

On this basis, the rapidly growing Chinese population in Batavia was the main reason for the breakdown of relations. Moreover, this condition was exacerbated by the loss of the sugar factories in Batavia, which later laid off workers, mostly Chinese. As a result, those who were unemployed were seen as disturbing the stability of the Dutch territory.

Third, riots in Batavia. The cause of the riot was none other than when the Dutch took the initiative to discipline all Chinese people. The steps taken by the Company were to ask all Chinese without exception to make a residence permit.

“… A proclamation was issued stating that all people who lived in Batavia for a long time or for a short time but did not have a permit had to obtain a permit from the Secretary of the Colonial Government by paying two rijsdaalder. This permit was processed within three weeks, ”it is written on page 40.

If they do not have a permit, they will be arrested and then deported to Sri Lanka or South Africa, which in fact were under VOC control. Unfortunately, rumors spread that those who were arrested for not having a permit were dumped into the middle of the ocean. Finally, some Chinese believers then instigated a revolt by attacking the sugar factories and VOC security posts.

The Dutch, who were outraged, began to seek out rebels after a few days. The heated situation turned the nuances of the rebellion into a bloody incident of looting and massacring more than 10 thousand Chinese people.

Fourth, the impact of mass slaughter. The Dutch act which hastily made a decision so that the mass slaughter could not be avoided, in fact it caused the Company to lose money. This was because there was almost a shortage of all goods, including foodstuffs in Batavia. In fact, sometimes there are no items at all at a time.

Even though the government had tried to replace the role of the Chinese with other residents, the VOC income still drastically decreased in the next few years. "The absence of Chinese citizens made the Batavian community suffer because of a shortage of foodstuffs and handicraft goods," he wrote on page 110.

Therefore, the reader can learn how cruel the Netherlands was at that time. the Dutch attitude that only thought about profit resulted in the death of other Chinese people, which had nothing to do with the rebellion of 1740.

Detail

Book Title: Tionghoa in Batavia and Huru Hara 1740

Author: Johannes Theodorus Vermeulen

First Published: 1938

Publisher: Bamboo Community

Number of Pages: 146

The English, Chinese, Japanese, Arabic, and French versions are automatically generated by the AI. So there may still be inaccuracies in translating, please always see Indonesian as our main language. (system supported by DigitalSiber.id)